Think you could be a scout? If I sent you coach's videotape from a high school football game in, say 1980, would you be able to tell me which quarterback went on to be a star in the NFL and which never even made it as a college player? There's no sound, the uniforms don't provide any insight, and neither kids puts up statistics that would reveal his future stardom.

I ask this question a lot. I ask casual fans. I ask writers. I ask pro coaches and personnel guys. What's most fascinating is that the closer I get to guys that actually have to make these kinds of decisions, the less likely they are to say "yes."

It's a question that interested me as I began to work on my football book, which came out last summer. I wanted to challenged the conventional wisdom about who the great football players of all time were. If Dick Butkus is the greatest linebacker of all-time, then it ought to be obvious to anyone who watches film of his games. Maybe film doesn't exist, or doesn't tell the full story. Fair enough, but then you at least ought to be able to give me some reasons why a player was so good. Tell me what it is about Red Grange that made him stand out. Explain why Jim Otto was the best lineman of his day.

It's a question that transcends sports. We learn about great works of art in the same way. Why is the Mona Lisa a great painting? What makes "Citizen Kane" one of the most important American films? If I think it's boring, am I just too unsophisticated to understand what I'm seeing?

All of these questions point toward the same issue? To what degree is "greatness" a measure of collective opinion and to what degree is "greatness" inherent. If you watch Citizen Kane for the first time tonight, will its greatness be obvious? Or is its greatness more about familiarity? Is it great because "people" have always said it was great.

I'm not the first to raise this question. In fact, it's one of the oldest epistomological debates. Is beauty a measurable fact (as Gottfried Leibniz asserted), or merely an opinion (David Hume), or is it a little of each, colored by the immediate state of mind of the observer (Immanuel Kant)?

In the spring of 2007, Washington Post reporter Gene Weingarten wanted to probe that ageless question in a modern setting. He convinced Grammy award winning classical violinist Joshua Bell to play at the entrance of a Washington D.C. subway station, posing as a run of the mill street performer. Bell isn't as recognizable as, say Brad Pitt, but he was a child prodigy who has, at the age of 39, becmone an internationally acclaimed virtuoso. His 2003 CD Romance of the Violin sold more than five million copies and remained at the top of classical music charts for 54 weeks. Bell's instrument was a 300-year-old Stradivarius violin, for which he had paid more than four million dollars. He played Carnegie Hall at 14. He has played for Kings and Queens. The cheap seats for one of his concerts go for around $100. Would folks walking past think he was just another busker, or would they recognize and appreciate the quality of Bell's performance?

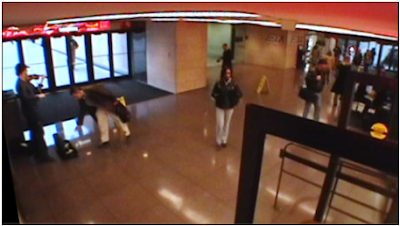

Violinist Joshua Bell playing at the L'Enfant Plaza subway station

Violinist Joshua Bell playing at the L'Enfant Plaza subway stationin Washington, D.C. on January 12, 2007. Bell is at far left.

Full video available at Washington Post website.

Weingarten started by posing the question to Leonard Slatkin, music director of the National Symphony Orchestra. What did he think would occur, hypothetically, if one of the world's great violinists had performed incognito before a traveling rush-hour audience of 1,000-odd people?

"Let's assume," Slatkin said, "that he is not recognized and just taken for granted as a street musician . . . Still, I don't think that if he's really good, he's going to go unnoticed. He'd get a larger audience in Europe . . . but, okay, out of 1,000 people, my guess is there might be 35 or 40 who will recognize the quality for what it is. Maybe 75 to 100 will stop and spend some time listening."

Slatkin was wrong.

Bell played for 45 minutes and more than a thousand people passed by. Just seven stopped to listen. The vast majority of folks didn't react at all to one of the world's greatest musicians playing a few feet away from them.

Of course, this phenomenon is not limited to music. Weingarten also interviewed one of the leading experts in the world of art.

Mark Leithauser has held in his hands more great works of art than any king or pope or Medici ever did1. A senior curator at the National Gallery, he oversees the framing of the paintings. "Let's say I took one of our more abstract masterpieces, say an Ellsworth Kelly, and removed it from its frame, marched it down the 52 steps that people walk up to get to the National Gallery, past the giant columns, and brought it into a restaurant. It's a $5 million painting. And it's one of those restaurants where there are pieces of original art for sale, by some industrious kids from the Corcoran School, and I hang that Kelly on the wall with a price tag of $150. No one is going to notice it. An art curator might look up and say: 'Hey, that looks a little like an Ellsworth Kelly. Please pass the salt.'"

Weingarten won a Pulitzer Prize for the article.